A poem’s essence in a novel

Two characters in my work-in-progress (a YA sf/f/mystery/thriller thing) take a class together in which they have to write poetry. She’s pretty good at it, he not so much.

So poems are on my mind, and since I’m just over the 10,000-word mark in the work-in-progress, it means I’m taking a step back to evaluate my plotting and dream up new plot twists (if you were paying attention to my plotter vs. pantser post, you’d know this). Part of stepping back is looking at favorite things I’ve read and written. Since I used to teach British Literature, I have these two poems, two of my faves of all-time, saved on my computer.

Emily Bronte’s is a fairly straightforward poem of mourning. Philip Larkin’s captures, for me, the very profound feelings I’ve had visiting old, spiritual places here and abroad. Each poem has the essence of somethingBronte’s “divinest anguish” and Larkin’s “serious”nessthat, given their contexts, I feel in my own writing. If only I had a comparable gift with words, I might be published already.

Do you have a favorite poem that speaks to you so strongly you feel it echoes the essence of what you write? If you’re a reader, not a writer, do you have a favorite poem whose essence is something you find in the novels you gravitate toward?

If you’ve never thought about your favorite poem this way, maybe you should.

Either way, I’d love it if you shared your favorite poem. I’m always looking for new things to speak to me.

Remembrance

by Emily Bronte

Cold in the earth, and the deep snow piled above thee!

Far, far removed, cold in the dreary grave!

Have I forgot, my Only Love, to love thee,

Severed at last by Times all-wearing wave?

Now, when alone, do my thoughts no longer hover

Over the mountains, on that northern shore;

Resting their wings where heath and fern-leaves cover

Thy noble heart for ever, ever more?

Cold in the earth, and fifteen wild Decembers

From those brown hills have melted into spring-

Faithful indeed is the spirit that remembers

After such years of change and suffering!

Sweet Love of youth, forgive if I forget thee

While the Worlds tide is bearing me along;

Other desires and other hopes beset me,

Hopes which obscure but cannot do thee wrong.

No later light has lightened up my heaven,

No second morn has ever shone for me:

All my lifes bliss from thy dear life was given-

All my lifes bliss is in the grave with thee.

But when the days of golden dreams had perished

And even Despair was powerless to destroy,

Then did I learn how existence could be cherished,

Strengthened and fed without the aid of joy;

Then did I check the tears of useless passion,

Weaned my young soul from yearning after thine;

Sternly denied its burning wish to hasten

Down to that tomb already more than mine!

And even yet, I dare not let it languish,

Dare not indulge in Memorys rapturous pain;

Once drinking deep of that divinest anguish,

How could I seek the empty world again?

Church Going

by Philip Larkin

Once I am sure there’s nothing going on

I step inside, letting the door thud shut.

Another church: matting, seats, and stone,

And little books; sprawlings of flowers, cut

For Sunday, brownish now; some brass and stuff

Up at the holy end; the small neat organ;

And a tense, musty, unignorable silence,

Brewed God knows how long. Hatless, I take off

My cycle-clips in awkward reverence,

Move forward, run my hand around the font.

From where I stand, the roof looks almost new-

Cleaned or restored? Someone would know: I don’t.

Mounting the lectern, I peruse a few

Hectoring large-scale verses, and pronounce

‘Here endeth’ much more loudly than I’d meant.

The echoes snigger briefly. Back at the door

I sign the book, donate an Irish sixpence,

Reflect the place was not worth stopping for.

Yet stop I did: in fact I often do,

And always end much at a loss like this,

Wondering what to look for; wondering, too,

When churches fall completely out of use

What we shall turn them into, if we shall keep

A few cathedrals chronically on show,

Their parchment, plate, and pyx in locked cases,

And let the rest rent-free to rain and sheep.

Shall we avoid them as unlucky places?

Or, after dark, will dubious women come

To make their children touch a particular stone;

Pick simples for a cancer; or on some

Advised night see walking a dead one?

Power of some sort or other will go on

In games, in riddles, seemingly at random;

But superstition, like belief, must die,

And what remains when disbelief has gone?

Grass, weedy pavement, brambles, buttress, sky,

A shape less recognizable each week,

A purpose more obscure. I wonder who

Will be the last, the very last, to seek

This place for what it was; one of the crew

That tap and jot and know what rood-lofts were?

Some ruin-bibber, randy for antique,

Or Christmas-addict, counting on a whiff

Of gown-and-bands and organ-pipes and myrrh?

Or will he be my representative,

Bored, uninformed, knowing the ghostly silt

Dispersed, yet tending to this cross of ground

Through suburb scrub because it held unspilt

So long and equably what since is found

Only in separation – marriage, and birth,

And death, and thoughts of these – for whom was built

This special shell? For, though I’ve no idea

What this accoutred frowsty barn is worth,

It pleases me to stand in silence here;

A serious house on serious earth it is,

In whose blent air all our compulsions meet,

Are recognised, and robed as destinies.

And that much never can be obsolete,

Since someone will forever be surprising

A hunger in himself to be more serious,

And gravitating with it to this ground,

Which, he once heard, was proper to grow wise in,

If only that so many dead lie round.

Plotter versus pantser

I don’t know how standard these terms are outside of my writing network, but for those who don’t know, a plotter is someone who plans or outlines their story ahead of time and a pantser flies by the seat of their pants, so to speak, and makes things up as they go along.

Some people are die-hard plotters or die-hard pantsers, but in my experience most writers are some parts each.

I’m probably one-third plotter and two-thirds pantser. I’m working on my third novel now, and although I’ve approached the actual execution of my ideas differently in each case, my creative process is still pretty much the same. I plan a little and then let the rest come as it comes.

For example, in my first novel, I knew the main character would be a young man in a Moses situationhe was born on the side that lost a war and without his knowledge was raised to be the elite of the side that won. I knew he had to have a Jean Valjean story of remarkable redemption. I knew that his planet’s population would be descendants of a space-travel accident, and that they would, one thousand years later, have split themselves into three societies of distinctly different moral codes.

I did not know at first the true nature of my character’s special sci-fi ability (what? you’d say, if you read the novel, his secret ability is the central concern of the story), or the circumstances of his family members he lost because of the war (what? the whole story is about reuniting them). I did not know of the existence of the secret societies or admiralty intrigue or extra-terrestrial beings that basically drive the entire plot. I did not know the ending or how to get there, only the nature of the choice the character would have to make.

With the basics of the characters and world-building fairly set, I come up with an inciting incident, and from there start writing. As I get a little ways into the story, it’s like turning a casual acquaintance into a dear friend. Spending time with my story brings us closer, and plot twists present themselves. So, basically, I begin plotting my story in earnest after I’ve written chapter two or three, and by this time I’m pretty sure I’ve figured out the ending. I’m always planning several steps ahead, but I’m hesitant to chart a firm course all the way through because I know that most of my best ideas come with timein the shower, in the carand only as I think through the consequences of the chapter I’ve just finished writing.

The consequence of pantsing much of the plot is that I have to do major revisions. A story must build to its climax, and since I never know exactly where I’m going to end up, I have to go back to the beginning and make sure the road is clear from page one. I do at least as much work revising as I do the original draft, and that works for me.

So, are you a plotter or a pantser? Has anything worked for you that might help another writer like me?

STORY-inspired plot chart

One of the most importantscratch thatTHE most important book I’ve read about writing is Robert McKee’s Story.

McKee’s book is based on his famous seminars he delivers world-wide and is actually for screenwriters, but his advice is completely relevant for novel writers. On his website, he says his alumni have won 35 Academy Awards (160+ Nominations) and 164 Emmy Awards (500+ Nominations). The dust jacket of my hardcover copy says works written, directed, or produced by his alumni include Batman Forever, Beauty and the Beast, E.R., Forrest Gump, Friends, Law & Order, Saving Private Ryan, Seinfeld, Sesame Street, Toy Story, and the X-Files, and my copy is something like eight years old.

Two important concepts I took from the book are the “gap” and “two goods/two bads.” Essentially, the “gap” opens up when a character takes action they expect to yield a certain result, but the reality turns out differently. Two goods/two bads refers to character choices, which are only meaningful if the choice is between two equally strong goods or two equally strong bads. To really understand these concepts, read the explanations and examples in McKee’s book.

Reading Story led to my creation of a “gap chart” for my first manuscript (science fiction set on a faraway planet). My main character, Aiden Carter, is an ambitious eighteen-year-old on the fast track to the equivalent of the presidency. His skeleton in the closet is his mother, who frequently breaks the law against charity. Here is the very top of the chart:

| Plot advances | What Aiden expects | What happens instead | Possible choices/ consequences | Decision/new direction | What is risked |

| Aiden Carter cheats in a track meet, next morning called to “principal’s” office. | Fears either a punishment for cheating or questions about his collapse on the track. | Questioned by the military government about his mother, Hannah Carter.INCITING INCIDENT | TWO GOODSTell truth-avoid getting in trouble.

Lie-protect mother from prosecution. |

Lies. | University honor status. |

| Aiden walks home.PROGRESSIVE COMPLICATIONS BEGIN | Hannah Carter is safe. (because his lies will protect her) | Hannah Carter is arrested anyway. | TWO GOODSDon’t testify-possibly prevent her conviction.

Testify-save his own career. |

Testifies. | Hannah Carter’s life. |

This chart goes on for twelve more rows with Aiden taking actions and having his world react unexpectedly, which then causes him to take more actions where more and more is risked. It is that far-right column that gives the story it’s drama. My “What is risked” column progresses from “university honor status,” through things like “his identity,” “his secret power,” “his life,” “the entire planet.” As you go further down my risk column the stakes for Aiden get higher and higher until the largest possible thing is at stake.

I made this gap chart after I had written the manuscript. It helped me see my story in a way that was much more useful than a mere outline of the plot. It’s one of the most important writing exercises I’ve ever done.

For me it had to be part of the rewrite, but a different writer might benefit from doing this exercise at the outset. Some entry soon I’ll write a few words on the plotting vs. pantsing question.

What I learned from The Boy From Ilysies

This is the second book in the Libyrinth trilogy by Pearl North, and I think the cover blurb from Realms of Fantasy is accurate: “Philosophical, powerful, captivating, and populated by memorable characters.”

Because of my own writing interests, it is the “philosophical” that draws me most to this story. Here is the first paragraph on the dust jacket of my copy: “On a world where the only ties to Earth appear to be the books stored and protected in the vast library known as the Libyrinth, a battle once raged between the Singers, who for generations beyond remembering relied on oral storytelling to transmit knowledge, and the Libyrarians, who dedicated their lives to preserving the wisdom stored in books.” The plot of the first book, Libyrinth, basically covers the war between those who believe in the written word and those who don’t.

But the trilogy is philosophical beyond matters of literacy. There are several societies in Pearl North’s world, and besides the question of literacy, these societies are defined by their cultural definitions of the roles of women and men. The Boy From Ilysies is primarily the story of Po, a young man raised in a society where men serve women. As an exile from his homeland, he struggles with his role as a man in a new society where men and women are equals. Expectations and cultural norms are questioned by many characters in the story as the characters from different walks of life try to understand each other.

This book is useful to me as an example of how characterization, world-building, and plot are intertwined. Several major plot points revolve around decisions characters make as a result of their cultural upbringing or reaction to that upbringing. For example, Po makes the mistake of falling into his old role of subservience to a woman and almost destroys the budding utopia he calls home. This disaster drives the plot for the rest of the novel. On a related note, I paid particular attention to how North’s characters speak of and think about the differences among them and the changes certain characters undergo throughout the book.

I also found this book useful because it contains one heck of a magical object. I can’t wait to see what happens with it in the final installment of the series.

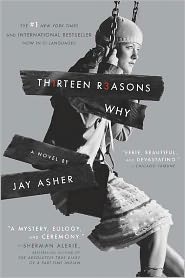

Graceling and Thirteen Reasons Why

Have you ever read a book and thought, “That’s what I’m trying to accomplish with my writing.” I can’t recall how many times I’ve felt this way after reading a book, but I can name two times in recent memory: reading Kristin Cashore’s Graceling (which I’ve already mentioned in a previous post) and reading Jay Asher’s Thirteen Reasons Why, both YA (young adult) novels.

I can’t remember how I came across Graceling, but I think it might have been by reading Calico Reaction’s review. Graceling has a medieval-ish fantasy setting and is the story of Katsa, a young woman with a “grace” or special talent. Her grace is to kill, and her uncle, the king, forces her to be his thug by sending her against his enemies. The story follows Katsa as she rebels against her uncle and undertakes an epic journey to save the kingdoms from an evil graceling much more powerful than she. Thought-provoking questions about power, its use and abuse, pervade the story, as does the adolescent’s search for identity. Katsa must discover the true nature of her grace and make a decision on how she is going to use it. Of course, as with most good YA, there’s also a compelling love story.

I do remember how Thirteen Reasons Why came to my attention. My grad school program requires all members to read a common book for each residency. One term, the book chosen was Thirteen Reasons Why. Although I didn’t attend that particular residency, the book sounded intriguing, and I decided to pick it up. Thirteen Reasons Why is set in modern day (and is mainstream, not fantasy) and follows Clay Jensen, a high school student whose classmate, Hannah Baker, committed suicide only weeks before. He comes home one day to find a set of audiotapes in a box. He quickly learns that the tapes were recorded by Hannah before she died and are her account of the thirteen reasons why she committed suicide. Clay has received the tapes because his name is in them.

Thirteen Reasons Why is told from Clay’s point of view, but his thoughts and actions as he listens to the tapes are interwoven with Hannah’s narrative. The story is heart-wrenching, and by the end the message is abundantly clearpeople need to think about their actions and need to work on performing kindnesses because you never know how another person might be suffering. Clay, a boy most parents would love to call “son,” is a good character to illustrate the message.

As far as my writing goes, I consider both of these books inspirations. Graceling is a YA book, but it’s tone is more straight fantasy than YA and the hefty questions of power are not typical YA fodder, so it was my inspiration for the very difficult task of completing my revision of Wishstone for a YA audience. Thirteen Reasons Why gave me some confidence that I can write a novel set in modern day. Since my first novel is set in outer space thousands of years in the future and my second novel is set in ancient Greece thousands of years in the past, I was doubting I had the skills to pull off modern day YA. I didn’t think a character I would enjoy spending a novel writing would appeal to a YA audience. Sometimes I feel YA characters in books are portrayed as the adults who write YA tend to see them, rather than how they are. I’m frequently dismayed by how YA characters in other media are portrayed as caricatures. Clay Jensen, however, is a thoughtful character who, I feel, has all the appropriate reactions to what he hears on Hannah’s tapes. He felt much more real to me than any YA character I’ve encountered in a long time.

Moral of the story: my current project is a YA fantasy set in modern day. I’m sure there’ll be updates . . .