What should high school students be reading?–follow-up

Because this website is getting so many hits from people Googling some variation of “What high school students should read,” I thought I would post this follow-up. (Original post here.) What follows is curriculum- and research-oriented.

When we were looking into redesigning the English curriculum where I taught, two sources were at the top of our list, and both have stated positions on kids and reading. The first is the Massachusetts Curriculum Frameworks, published by the Massachusetts Department of Education (obviously my school was in Massachusetts, but you can find the equivalent for your state). The second is the National Council of Teachers of English, of which I am a member (and would recommend you become a member, too, if you are an English teacher at any level). Although I post a couple of passages below, you might consider researching at each source more thoroughly.

From the Massachusetts Frameworks in Language Arts:

Note on range and content of student reading: To become college and career ready, students must grapple with works of exceptional craft and thought whose range extends across genres, cultures, and centuries. Such works offer profound insights into the human condition and serve as models for students own thinking and writing. Along with high-quality contemporary works, these texts should be chosen from among seminal U.S. documents, the classics of American literature, and the timeless dramas of Shakespeare. Through wide and deep reading of literature and literary nonfiction of steadily increasing sophistication, students gain a reservoir of literary and cultural knowledge, references, and images; the ability to evaluate intricate arguments; and the capacity to surmount the challenges posed by complex texts.

From the National Council of Teachers of English:

In order to make sure that all individuals have access to the personal pleasures and intellectual benefits of full literacy, NCTE believes that our society and our schools must provide students with:

- access to a wide range of texts that mirror the range of students’ abilities and interests;

- ample time to read a wide range of materials, from the very simple to the very challenging;

- teachers who help them develop an extensive repertoire of skills and strategies;

- opportunities to learn how reading, writing, speaking, and listening support each other;

- and access to the literacy skills needed in a technologically advanced society.

You may also benefit from looking at NCTE’s position statements on literature.

Also note that while we were researching effective ways to update our curriculum, we spent a lot of time on the websites of other schools in our area and of the top-performing schools in our state. We looked at such variables as what schools offered for required courses vs. electives, what texts were taught at each grade level and each competency level, and how much room there was for individual teachers to select books that worked best in their classroom (as opposed to everyone, across the course, reading lock-step identical texts). You may find it quite eye-opening to see what is being taught in the schools near you.

There are many reasons you might be researching “high school reading choices.” Perhaps you are a high schooler looking for the title of a worthwhile read (in which case, I’m sorry this post isn’t helpful), or perhaps you are questioning the curriculum at your school. Maybe you are a parent concerned about your child’s reading at school or at home. Maybe you are a teacher or administrator looking to reform your school’s curriculum. Although schools vary widely in their approach to change, I found my experience trying to update the curriculum a little frustrating. In the end I had to turn to alternative methods for introducing contemporary texts. The most important alternative was my classroom library, which I might address in another post.

High concept?

High concept fiction is that which can be pitched in very few words and has mass, easily recognizable appeal. The term “high concept” has filtered into the publishing world from the movie world.

Here is a very succinct set of examples from Nathan Bransford to illustrate high concept versus not:

Kid wins a golden ticket to a mysterious candy factory? High concept.

Wizard school? High concept.

There’s this guy who walks around Dublin for a day and thinks about a lot of things in chapters written in different styles and he goes to a funeral and does some other stuff but otherwise not much happens? Not high concept.

As I research agents for submission of my latest manuscript (#3), I find myself questioning whether or not my story is, in fact, as high concept as I intended. My story isn’t Snakes on a Plane, which tells you all you need to know from the title.

I found a great line from Steve Kaire that has me thinking: “Non-High Concept projects can’t be sold from a pitch because they are execution driven. They have to be read to be appreciated and their appeal isn’t obvious by merely running a logline past someone.”

I’m not willing to divulge the premise or plot of my manuscript on the internet (sorry), but I will say that I’ve had one heck of a time boiling it down to a logline that really conveys the essence of the story. Could this be because the strength of my story is in its execution, not its concept? Or am I just a failure at coming up with a great logline?

By contrast, I know with certainty that my second manuscript IS high concept and my first is NOT. (And my fourth, my WIP, IS.) Why am I having such a difficult time determining the status of manuscript #3?

Well, I’ll be attending a conference later this month with workshops led by literary agents evaluating query letters and opening pages, and I hope to have my question answered.

In the meantime, some of you reading this post have read said manuscript #3. Thoughts?

* * *

Here are a few links to info on high concept fiction:

http://blog.nathanbransford.com/2010/08/what-high-concept-means.html

http://www.writersstore.com/high-concept-defined-once-and-for-all

http://misssnark.blogspot.com/2006/06/high-concept.html

http://www.amazon.com/High-concept-literary-fiction/lm/R2V1Y7KSZU48B0

http://www.rachellegardner.com/2011/08/what-is-high-concept/

http://waxmanagency.wordpress.com/2009/02/06/recipe-for-success-high-concept/

http://www.professorbeej.com/2012/02/high-concept-vs-high-character.html

What should high school students be readingclassics or books they enjoy?

Personally, I wish the answer were. . . What do you mean? Don’t high school kids enjoy the classics?

I always have enjoyed them. I loved, for example, The Red Badge of Courage and The Scarlet Letter when I read them in high school. I was an English major in college, so it would have been torture for me to take all the required courses if I didn’t enjoy the books studied in them. As an English teacher I did a lot of enjoyable re-reading of classics.

Yet being an English teacher taught me pretty quickly that most high school students don’t enjoy “classic” literature. In fact in the suburban, middle-class, mostly-white school where I taught, most students didn’t enjoy reading at all. If I hadn’t had the luxury of teaching the AP class, where just about all of the students admitted they at least liked to read, I might have fallen into a deep depression at the attitude of my other college-bound students, some of whom proudly declared that they had never read a book for school in their lives. They had made it to the twelfth grade by plagiarizing and reading SparkNotes. I honest-to-God once had parents come in to argue to the principal that their son shouldn’t receive a zero for work done with SparkNotes instead of the actual book. If the answers are in SparkNotes, the parents argued, and their son “researched” them, why shouldn’t he receive full credit? Never mind that, ahead of time so there would be no misunderstandings, I specifically forbade the class from using any source other than the book. The boy cheated anyway and expected to get an A.

There is much I could say about teacher education or teacher quality or the million things about teaching in a public school that hamper teachers’ ability to do what they know to be right and effective in a classroom. I could rail against TV, video games, and the internet. I could cite additional examples of unsupportive parents. Although it’s true that there could be improvements made on all of these fronts if we want children to read, still some children do read. The bottom line is that not everybody is a reader, just as not everybody is an athlete or an artist or a good friend. Some people just don’t like to read.

But that is no excuse for educators not to have high reading expectations. (I cringe as I write this because I know how really, truly hard it can be to get reluctant, plagiarism-entrenched, entitled students to do honest reading. I do not know first-hand how difficult it is to get disadvantaged students to read, because the issues with poor students are different than in the middle-class suburban school where I taught, but I do believe teachers when they say it’s hard work.) For a long time it seemed schools resisted the idea of giving kids books they enjoyed because the classics were better educational tools. Now I see schools adding those enjoyable reads, and I have mixed feelings. (Here I cringe again because I write, I like to think, those enjoyable reads, and I feel that there is value in reading for pleasure.)

There is a report out from Renaissance Learning stating that high school students, on average, read texts for school (both self-chosen and assigned) that average at a fifth grade level. This is in language difficulty and complexity, not content, mind you, but still. This statistic is disappointing to me.

You can find a million sources out there to tell you why kids should read books. Heck, why people of all ages should read books. Books expand the imagination. They develop critical thinking. They encourage empathy. They teach about otherness. They teach about the common human condition. They give pleasure. Etc. Etc. Etc.

You can also find a million sources out there to tell you what books kids should read in school. Here are some quotes from students themselves that I found online (Here is the original blog post where I found these quotes.):

As a student, I can firmly say that just because a book has endured through generations does not make it relevant to my generation. The veil of time often blinds young readers to a books meaning.-Jacob Stroud

Current required readings often make students skip the book and go straight to the movie or use SparkNotes to pass the test.-Olivia Reed

By exposing students to more modern literature they can relate to, they may come to view reading as cool or enjoyable, rather than only as homework or something that nerds do.-Ashley Monroe

If you go here, you can read the full answers given by these three students, which are actually much more thoughtful than these quotes might suggest. I would like to focus for the moment, though, on the ideas in these three excerpts alone because, unfortunately, I have heard these very arguments made by adults who should have the benefit of a wider perspective.

The idea behind the first quote drives me wild. Irrelevant? The moral question of responsibility for the bestowing (or ending) of life? (Frankenstein) The question of whether our circumstances are determined by a higher power or by ourselves? (King Lear) The question of what, exactly, makes a person worth marrying? (Pride and Prejudice) A young person who is struggling with the more complex style of older literature can be forgiven the difficulty in seeing the meaning in the text itself. It is the responsibility of the school to guide them past writing style (actually, I would argue, to guide them toward appreciation of style) and toward relevance.

The second quote could have been said by any number of students at the school where I taught. This is simple immaturity in the form of lack of personal responsibility. I didn’t cheat. The required readings made me skip the book and go straight to the movie or use SparkNotes. This is a very difficult challenge for an educator to overcome. Where I taught, a student saying such a thing would be just as likely to cheat on reading a book of their own choosingin fact, many students tried to do just that and would be angry at meat MEwhen their cheating was discovered.

The third quote has potential as an argument, but it is only the beginning, which I will expand upon in a sec.

So what should high school students be reading? In my humble opinion, anything that challenges them.

Challenge them to expand their vocabulary and decipher complex sentence structure. Challenge them to consider a new idea. Challenge them to view something from another’s perspective, from another era’s perspective. Challenge them to stick through a long book to the end. Challenge them to analyze, apply, synthesize. Challenge them to grow, to understand this world and their place in it. Challenge them to enjoy being the “nerdy” type who likes reading books!

School is for learning and challenges are the vehicle for learning. High school students should not be assigned books that fit snuggly into their comfort zone. To use a running metaphor . . . if you’re an 800 runner who races the 800 every meet, it does you good to challenge yourself to the longer 1600 or the faster 400 once in a while. The endurance or speed you pick up from going outside your comfort zone helps you grow as an 800 runner. Similarly, high school students have a reading comfort zone, a type of book they “enjoy.” Reading something that challenges them will affect how they approach the next book they read in their comfort zoneit will help them to see things in the text they might not have noticed otherwise, therefore giving them greater opportunity to grow from everything they read, even if they initially choose texts for their entertainment value only.

Now, I don’t think it’s useful to lay down the law and say, “They must read classics! Only classics are challenging! Everything else is a waste of time!”

I also don’t think it’s useful to say, “Let them read what they want! At least they’re reading!”

It’s likewise unhelpful to state simply, “They should read a mix.”

So much depends on the way the material is handled in the class. It does little good to assign challenging reading when the teacher ends up supplying all the insight, all the “right” answers, and it does little good to let students pick their own books if the teacher can’t then engage them in conversation about what they read.

There are many ways to approach teaching challenging texts (here I mean the “classics”), but I’m currently a believer in what I’ll call, because I’m quoting Barry Gilmore below, the “gateway and destination” approach, best explained in an article written by Gilmore in the above referenced Renaissance Learning report. Here is an excerpt from that article:

“The works students choose are largely what I think of as gateway novels and plays; they introduce themes and stylistic devices similar to those in classic works but often in a less urbane or nuanced manner. The Giver and The Hunger Games are gateways. They open the door to thinking about issues such as the rights of citizens to resist or the value of human relationships in a power-driven society. Julius Caesar, on the other hand, is a destination: a place where students, with their teachers, can investigate the same fundamental themes in depth. But the leap from the former works to the latter is a broad one. It requires the bridge of discussion and reflection.”

I would love to see more high schools pairing “accessible” works with “classic” ones. I like that more and more high schools are seeing the value in using popular YA literature as a teaching tool, and I appreciate that works today are encouraging more and more reluctant readers to read. I found value in having popular works in my classroom, but not at the expense of the challenge classic literature provides.

I once had a student, as her AP project, do a comparison of Paradise Lost (which we read together as a class) and Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy (which she read on her own and which is supposed to be a children’s version of Paradise Lost). I wish I could produce the paper for you to read her excellent insights. It was the kind of work I wish more kids had the opportunity to do.

Not every child is going to love the classics. Not every child is going to love reading. That doesn’t mean reading isn’t good for them, or that they can’t learn to love books, or that educators shouldn’t try to meet them on their level and progressively challenge them to understand things they might not seek to understand otherwise.

So the short answer to the question posed in this post’s title?

Yes.

P.S. I wrote a follow-up to this post that discusses sources I used to research a high school curriculum book list: http://www.jenbrookswriter.com/2012/06/09/what-should-high-school-students-be-reading-follow-up/.

I also mention a few specific titles for a classroom library in this post:http://www.jenbrookswriter.com/2012/06/25/books-for-high-school-kids-building-a-classroom-library/.

And it seems I couldn’t help but mention the subject again:http://www.jenbrookswriter.com/2013/09/17/thoughts-after-reading-insurgent/.

* * * * *

Articles linked in this post:

“Updating High School English” by LaToya Jordan: http://therumpus.net/2011/07/updating-high-school-english/

“Is the Literature in High School Too Cemented in the Past?” by Stroud, Reed, and Monroe: http://www.mlive.com/opinion/kalamazoo/index.ssf/2011/07/is_the_literature_covered_in_h.html

Renaissance Learning report (you have to click the link “Download your copy here” to get the pdf of the report): http://www.renlearn.com/whatkidsarereading/

Articles for further reading:

“Teaching Kids, Books, and the Classics” by Monica Edinger: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/monica-edinger/teaching-classics-kids_b_1191115.html

“Against Walter Dean Meyers and the Dumbing Down of Literature: ‘Those Kids’ can read Homer” by Alexander Nazaryan: http://www.nydailynews.com/blogs/pageviews/2012/01/against-walter-dean-myers-and-the-dumbing-down-of-literature-those-kids-can-read-h

“High School Students Aren’t Reading Books by Choice or Assignment” by Maureen Downey: http://blogs.ajc.com/get-schooled-blog/2012/04/12/high-school-students-arent-reading-challenging-books-by-choice-or-assignment/?cxntfid=blogs_get_schooled_blog

“Leveling Up and Keeping Score: High School Students Reading at 5th Grade Levels, Report Says” by Becky O’Neil: http://www.yalsa.ala.org/thehub/2012/04/03/leveling-up-and-keeping-score-high-school-students-reading-at-5th-grade-levels-report-says/

“American High School Students are Reading Books at 5th-Grade-Appropriate Levels: Report: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/03/22/top-reading_n_1373680.html#s805920&title=20_Marked_A

Upmarket

I’m wondering how many of you out there (who are not of the writing/publishing world) have heard of the word “upmarket.” It’s one of a bazillion terms that can be used to categorize a book, but there is no section at the local bookstore for it. It’s also a type of fiction that agents, and presumably publishers, are looking for writers to write, since a goodly number of agents I’ve been researching claim they want to represent it.

So what is upmarket fiction?

The simplest answer is that it’s a cross between literary and commercial fiction. Again, in simplest terms, literary fiction tends to be character-oriented and use artistic language, while commercial fiction tends to be plot-oriented and appeal to a wide audience (and generally falls into a genre such as romance, mystery, thriller, science fiction, fantasy, etc.).

Here is a definition of “upmarket” from the blog of book editor Robb Grindstaff: “From an audience perspective, upmarket means fiction that will appeal to readerswho are educated, highly read, and prefer books with substantive quality writing and stronger stories/themes. Upmarket describes commercial fiction that bumps up against literary fiction, or literary fiction that holds a wider appeal, or a work straddles the two genres.”

Literary agent Sarah LaPolla has this to say about upmarket fiction on her blog: “‘Upmarket’ fiction is where things get tricky. Books like The Help, Water for Elephants, Eat, Pray, Love, and authors like Nick Hornby, Ann Patchet,and Tom Perrotta are considered ‘upmarket.’Their concept and use of language appeal to a wider audience, but they have a slightly more sophisticated style than genre fiction and touch on themes and emotions that go deeper than the plot.”

I have heard upmarket fiction referred to as fiction that’s appropriate for book club discussion.

I identify my style with the concept of “upmarket.” I can write (I think) a decent sentence, sometimes a highly effective sentence, maybe even the rare beautiful sentence, but the pleasure I derive from writing doesn’t come as much from wordcraft as from themecraft (especially), plotcraft, and charactercraft. My strengths as a writer lie much more to the “idea” side of writing than to the “art” side. As an English major, creative writing MFA, and 14-year English teaching veteran, I am decently well-read, fairly well-educated, and like my fiction (whether I’m reading it or writing it) to make me think for days or weeks after I read “the end.”

HOWEVER. I object to the word “upmarket.” It has a connotation of snobbery to me. It implies that there is a part of the literary market (i.e. there are readers) who are “up,” i.e. “higher,” i.e. “better” because where there is an “up” there is a “down.” Is there one among you who doesn’t picture commercial fiction looking up from the bottom rung of the ladder while literary fiction waves from the top? Do you see “up”market fiction climbing down from literary heights or up from commercial doldrums?

I am sensitive to this literary versus commercial fiction argument, obviously. I grow livid when I hear literary writers sling the poop at commercial writers and commercial writers sling it at literary writers. And the poop does sling both ways. I am so tired of hearing people on high horses make derogatory comments about the writing quality of commercially successful novelists (aka Dan Brown, Stephanie Meyer, even J.K. Rowling) and other people on other high horses saying literary novels are too busy worrying about words to care about plot (yeah, even if true, SO WHAT? ). The truth is there are a variety of readers out there and a variety of writers, and thankfully the world has been forged by the Almighty in such a way that there are books to satisfy everyone’s taste. When I hear literary versus commercial arguments, I am often reminded of those bullies in the schoolyard who have to tear others down to build themselves up.

And then there are more recent folks who like labeling themselves upmarket because it’s better than being literary or commercial. These writers believe themselves the perfect cross between being the 1% and the 99%, too good to be purely literary because they can do plot, and too good to be commercial because they can do fine wordcraft. (Did I mention above that I think my work is upmarket?)

Of course, upmarket is also just a word, just an adjective, no arrogance attached.

I have wondered off my topic. Such is passion.

Although upmarket fiction is a cross between literary and commercial, that doesn’t mean it necessarily appeals to every literary or commercial reader. It’s something in between, for those folks who like to read and write in between. In case you were wondering.

And can there be “upmarket YA”? I’ve never heard the term. YA is YA, even though the books on the YA shelves are just as much literary, commercial, or upmarket as the rest of the fiction world. I’m not talking “crossover” here (which is when YA books also appeal to OAs). I’m saying different young adults prefer to read different things. Where do you think all those adult readers with discriminating tastes come from?

Thoughts?

Here are some websites to check out if you want to read more:

Book editor Robb Grindstaff’s blog (mentioned above): http://robbgrindstaff.com/category/upmarket-fiction/

Literary agent Sarah LaPolla’s blog (mentioned above): http://bigglasscases.blogspot.com/2012/01/literary-vs-commercial.html

Writer Margaret Duarte’s blog: http://enterthebetween.blogspot.com/2010/08/upmarket-fiction-where-commercial-and.html

Novel Matters (six contributing writers) blog: http://www.novelmatters.com/2009/04/upmarket-fiction-non-genre-genre.html

Absolute Write Water Cooler (discussion site for writers and other book professionals): http://absolutewrite.com/forums/showthread.php?t=90147

Update: blog identity and where I’m at Part 4

I started this blog as part of my effort to build a writing career. Since I am not-quite-published-yet, I have a pretty small regular readership. One might say that the only way to grow a readership is to post good content regularly, and one would be right. However, with all the effort I’m devoting to writing a new manuscript and researching agents for the last manuscript, I’m finding it hard to post as regularly as I’d like.

That said, I’ve been studying my Google Analytics reports and have found that a fair bit of non-regular-readership traffic does land here, and from the search parameters listed, it seems this is mostly because of research on literary topics. It’s hard to tell if such users find what they need here, but it’s made me think that, for now, I will focus on posts with an academic bent and a short list of resources for further reference. If you have a better idea, I’m all ears.

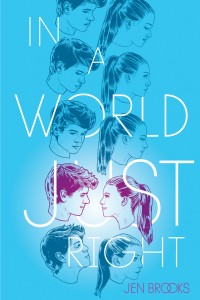

As for “where I’m at,” I’ll be brief. World Maker, my third manuscript, is on submission with agents. While I wait for the process to play out on World Maker, I’ve started research for a new story, and in the tradition of making each new project something new and different for me, this story requires a bit of New England historical research and some education on how to craft a mystery. I’m not sure about much except the basic concept and set-up, but I’m at least having fun seeing where it goes.

In summary:

manuscript #1: Prosorinos futuristic science fiction story, set on another planet, multiple POV but largely focused on two teenage boys, 169,000 words

manuscript #2: Wishstone alternate history fantasy, set in ancient Greece, single POV of teenage girl, 90,000 words

manuscript #3: World Maker comtemporary “psychological” fantasy (and love story), single POV of teenage boy, 93,000 words

manuscript #4: untitled contemporary mystery/fantasy/alternate history, ensemble cast